ANÁLISE ESTATÍSTICA

Tipos de testes estatísticos indicados para cada análise

| HIPÓTESE/OBJETIVO DA ANÁLISE | TESTES PARAMÉTRICOS | TESTES NÃO-PARAMÉTRICOS |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de 1 grupo com algum valor de referência. | One-Semple T Test. | Wilcoxon One-Sample. |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de 2 grupos distintos (amostras não pareadas). | T Student Independente. | Mann Whitney U. |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de 1 grupo avaliado em dois momentos (amostras pareadas). | T Student Pareado. | Wilcoxon Pareado. |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de mais de 2 grupos distintos (amostras não pareadas). | Kruskal-Walis. | |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de 1 grupo avaliado em mais de dois momentos (amostras pareadas). | ANOVA Medidas Repetidas. | Friedman. |

| Comparar as medidas de tendência central de 2 ou mais grupos avaliados em 2 ou mais momentos. |

ANOVA Fatorial de medidas repitadas ou Mista; MANCOVA; |

|

| Analisar se as frequências de distribuição de uma variável categórica se ajustam as frequências previstas por um modelo teórico | Qui-Quadrado de aderência (uma amostra); | |

| Analisar se há associação entre as frequências de variáveis categóricas. | ||

| Analisar se há associação/correlação entre as medidas de tendência central de dois grupos. | Coeficente de Pearson. | Coeficiente de Spearman. |

| Investigar a relação existente entre 1 variável independente e 1 variável dependente contínua. | Regressão Linear Simples. | |

| Investigar a relação existente entre mais de uma variável independente e 1 variável dependente contínua. | Regressão Linear Múltipla. | |

| Investigar a relação existente entre 1 variável independente e 1 variável dependente categórica dicotômica. | Regressão Logística Simples. | |

| Investigar a relação existente entre 1 variável independente e 1 variável dependente categórica com mais de dois níveis. | Regressão Logística Multinomial. | |

| Investigar a relação existente entre 1 variável independente e 1 variável dependente categórica ordinal. | Regressão Logística Ordinal. | |

| Avaliar a confiabilidade/reprodutibilidade (reliability) dos escores de variáveis contínuas entre diferentes instrumentos de medida, ou observadores, como também a concordância entre o mesmo instrumento de medida, ou observador, em momentos diferentes. |

Alfa de Cronbach (α); |

|

| Avaliar a concordância/confiabilidade (agreement) dos escores de variáveis categóricas dicotômicas obtidas por um observador/instrumento em dois momentos ou entre dois observadores/instrumentos em um único momento. | Kappa de Cohen (κ) . | |

| Avaliar a concordância/confiabilidade (agreement) dos escores de variáveis categóricas ordinais obtidas por um observador/instrumento em dois momentos ou entre dois observadores/instrumentos em um único momento. | Kappa Ponderado (weighted). | |

| Avaliar a concordância/confiabilidade (agreement) dos escores de variáveis categóricas obtidas por mais de dois observadores ou momentos. | Kappa de Fleis. | |

| Analisar a normalidade dos dados (análise univariada). | Shapiro-Wilk. | |

- Anotações para análise estatística <Clique aqui>.

Plano de análise estatística (planejamento estatístico)

- Hernández G et al. Plano de análise estatística para o estudo do tratamento precoce baseado em metas com utilização de uma visão fisiológica holística – estudo ANDROMEDA-SHOCK: um estudo randomizado e controlado. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(3):253-263. <https://www.scielo.br/j/rbti/a/GvWCBBJYyNhmtLqp34jFxKq/abstract/?lang=pt>.

Avaliação da normalidade dos dados

- Miot HA. Avaliação da normalidade dos dados em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J vasc bras. 2017;16:88–91. <http://www.scielo.br/j/jvb/a/FPW5hwZ6DTH4gvj5mJYpt6B/?lang=pt>.

- Torman VBL et al. Normalidade de variáveis: métodos de verificação e comparação de alguns testes não-paramétricos por simulação. Rev HCPA & Fac Med Univ Fed Rio Gd do Sul. 2012;227–37. <https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-834411>.

- Ghasemi A, Zahediasl S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: a guide for non-statisticians. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Spring;10(2):486-9. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23843808/>.

Estatística Descritiva

- FEIJOO, AMLC. A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, 109p. Disponível em: SciELO Books <https://static.scielo.org/scielobooks/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489.pdf>.______. Introdução. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 1-3. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-02.pdf>.

- ______. Distribuição de frequência. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 6-13. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-04.pdf>.

- ______. Medidas de tendência central. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 14-22. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-05.pdf>.

- ______. Medidas de dispersão. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 23-27. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-06.pdf>.

- ______. Medidas separatrizes. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 28-30. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-07.pdf>.

- FERREIRA, A.R.S. A importância da análise descritiva. Rev. Col. Bras. Cir. vol.47 Rio de Janeiro 2020. Epub 12-Ago-2020. <https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0100-69912020000100753&lng=pt&nrm=iso&tlng=pt>.

- RODRIGUESA, C.F.S.; LIMAB, F. J. C.; BARBOSA, F. T. Importância do uso adequado da estatística básica nas pesquisas clínicas. Rev. Bras. Anestesiol. vol.67 no.6 Campinas Nov./Dec. 2017. <https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0034-70942017000600619&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt>.

- Vetter TR. Descriptive Statistics: Reporting the Answers to the 5 Basic Questions of Who, What, Why, When, Where, and a Sixth, So What? Anesth Analg. 2017 Nov;125(5):1797-1802. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28891910/>.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect <https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06>.

|

Estudo transversal Ex. https://www.scielo.br/j/reben/a/WDRM3Wy3KNjxDYBCzxk4Ltm/?lang=pt Os dados foram digitados em dupla entrada no programa Excel®. Para verificar inconsistências, foram sobrepostos os bancos por meio do software Microsoft Excel 2016. Dados não recuperáveis foram registrados no banco como missing. A análise dos dados foi feita no programa Stata, versão 15.0. Inicialmente, foi realizado o teste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov com correção de Lilliefors para verificar a normalidade e as variáveis com p-valor>0,05 foram consideradas com distribuição normal (Ghasemi A; Zahediasl S, 2012). Em seguida, foi feita a análise descritiva das variáveis sociodemográficas relacionadas à morbidade e à dor, expressas em frequência absoluta (n) e relativa (%), mediana, intervalo interquartil (IQ) e valores de mínimo e máximo. Os domínios do WHOQOL-OLD foram ponderados com base em suas respectivas sintaxes e expressos em valores de média e desvio-padrão (DP). Ex.: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbort/a/Q4kDXK4zWPd5WgRYFKG6VGN/?lang=pt# Os dados foram analisados no programa Jamovi, versão 2.7.12. Inicialmente, foi realizada uma análise exploratória dos dados para identificar dados faltantes, erros de digitação e valores inconsistentes. Depois, esses dados foram corrigidos com base em prontuários ou registros em papel. A normalidade foi avaliada pelo teste de Shapiro-Wilk. Foi realizada análise descritiva univariada, sendo as variáveis categóricas apresentadas por meio de frequências absoluta (n) e relativa (%) e as variáveis numéricas descritas por medidas de tendência central e de variabilidade, sendo apresentada a média e desvio-padrão (DP) para as variáveis com distribuição normal e mediana e intervalo interquartil (IQ) para as variáveis com distribuição não normal.

Ensaio clínico Ex. PMID: 34271271 We performed all the analyses in an intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who had undergone randomization and interventions. Descriptive statistics were applied to present the characteristics of each group with mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile), or the number of cases (%). Ex. PMID: 34271271 We performed all the analyses in an intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who had undergone randomization and interventions. Descriptive statistics were applied to present the characteristics of each group with mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile), or the number of cases (%). All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2010). |

Conversão de valoresEstimar a média e DP a partir da mediana e IQ <Clique aqui> Estimar o DP a partir do erro padrão ou IC95% <Clique aqui> Estimar o DP a partir do p-Valor e t-Valor <Clique aqui>. Estimar o IC95% para médias e proporções <Clique aqui> Combinar médias e DPs em um único grupo <https://www.statstodo.com/CombineMeansSDs.php> |

Tabelas

- FEIJOO, A.M.L.C. Organização e interpretação da tabela. In: A pesquisa e aestatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 4-5. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-03.pdf>.

- Spriestersbach A et al. Descriptive statistics: the specification of statistical measures and their presentation in tables and graphs. Part 7 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009 Sep;106(36):578-83. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19890414/>.

| Análise de tabelas de contingência foi utilizada para a investigação de variáveis categoriais, com o resultado estatístico sendo distribuído como qui-quadrado de Pearson (c2). Taxas de sensibilidade, especificidade, valor preditivo positivo (vpp), e valor preditivo negativo (vpn) foram estimadas a partir de tabelas de contingência 2X2. |

Gráficos

- Hertel J. A picture tells 1000 words (But most results graphs do not): 21 alternatives to simple bar and line graphs. Clin Sports Med. 2018;37(3):441–62. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29903385/>.

- Martinez EZ. Description of continuous data using bar graphs: a misleading approach. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48(4):494–7. <https://www.scielo.br/j/rsbmt/a/KfzwDkz5XkVyCjy3TRY8qcn/?lang=en>.

- Spriestersbach A et al. Descriptive statistics: the specification of statistical measures and their presentation in tables and graphs. Part 7 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009 Sep;106(36):578-83. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19890414/>.

- Pupovac V, Petrovecki M. Summarizing and presenting numerical data. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2011;21(2):106-10. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22135849/>.

- Tipos de gráficos:

Estatística Analítica ou Inferencial

- FEIJOO, A. M. L. C. Objetivos da inferência estatística. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 31-38. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-08.pdf>.

- ______. Etapas da pesquisa científica. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 39-42. < http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-09.pdf >.

- ______. Provas estatísticas. In: A pesquisa e a estatística na psicologia e na educação [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Centro Edelstein de Pesquisas Sociais, 2010, pp. 43-69. <http://books.scielo.org/id/yvnwq/pdf/feijoo-9788579820489-10.pdf>.

- Contador JL, Senne ELF. Testes não paramétricos para pequenas amostras de variáveis não categorizadas: um estudo. Gest Prod. 2016;23:588–99. <https://www.scielo.br/j/gp/a/wP5y4sntLmLyzLH7bHPy9ZF/>.

- PAES, A.T. Itens Essenciais em Bioestatística. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. vol.71 n.4 São Paulo Oct. 1998. <https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0066-782X1998001000003>.

- du Prel JB et al. Confidence interval or p-value?: part 4 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009 May;106(19):335-9. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19547734/>.

- Norman GR, Streiner DL. Do CIs give you confidence? Chest. 2012 Jan;141(1):17-19. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22215826/>.

- Victor A et al. Judging a plethora of p-values: how to contend with the problem of multiple testing–part 10 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 Jan;107(4):50-6. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20165700/>.

Análise EstatísticaEstatística no Excel REAL STATISTICS USING EXCEL <https://www.real-statistics.com/>. Suplementos <https://drive.google.com/file/d/19w1hJTiTG04uA3fXoyamZBVyPRwJEJtl/view?usp=sharing>. Estatística no R e RStudio Canal do Prof. Ronaldo Lima Jr. (UNB) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sjX4rPfA_H0&list=PLzkA7H-mNfYhdbUe1e0FMpJDdLj1585zq>. Tutoriais para análise estatística no SPSS Análise descritiva e inferencial (testes de associação e comparação) <Clique aqui>. Análise testes de comparação <Clique aqui>. <Clique aqui>. Análise testes de Regressão (linear e múltipla) <Clique aqui>. Análise testes de Regressão (linear e logística) <Clique aqui>. Análise testes de Validade e Confiabilidade <Clique aqui>. Análise da pontuação do WHODAS 2.0 <Clique aqui>. Tutorial para metanálise Metanálise utilizado o RevMan <Clique aqui>. |

Imputação de dados perdidos

- Ferreira JC, Patino CM. Perda de seguimento e dados faltantes: questões importantes que podem afetar os resultados do seu estudo. J bras pneumol. 2019;45:e20190091. <https://www.scielo.br/j/jbpneu/a/6zXp3jWPyw5bCdMQsmS8dFN/?lang=pt>.

- Miot HA. Valores anômalos e dados faltantes em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J vasc bras. 2019;18:e20190004. <https://www.scielo.br/j/jvb/a/mygXvfCbQ6q4Dz5DtFbkV4D/?lang=pt>.

- Carpenter JR, Smuk M. Missing data: A statistical framework for practice. Biom J. 2021 Jun;63(5):915-947. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33624862/>.

- Dong Y, Peng CYJ. Principled missing data methods for researchers. Springerplus. 2013 May 14;2(1):222. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23853744/>.

- Lachin JM. Fallacies of last observation carried forward analyses. Clin Trials. 2016 Apr;13(2):161-8. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26400875/>.

Intention to treat analysis and per protocol analysis

- Intention to treat analysis and per protocol analysis: complementary information. Prescrire Int. 2012 Dec;21(133):304-6. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23373104/>.

- Gupta SK. Intention-to-treat concept: A review. Perspect Clin Res. 2011 Jul;2(3):109-12. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21897887/>.

- Salim A et al. Comparison of data analysis strategies for intent-to-treat analysis in pre-test-post-test designs with substantial dropout rates. Psychiatry Res. 2008 Sep 30;160(3):335-45. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18718673/>.

- Streiner D, Geddes J. Intention to treat analysis in clinical trials when there are missing data. Evid Based Ment Health. 2001 Aug;4(3):70-1. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12004740/>.

Last observation carried forward

- Streiner DL. Statistics commentary series: commentary #3–last observation carried forward. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014 Aug;34(4):423-5 <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24911436/>.

- Nunes LN, Klück MM, Fachel JMG. Uso da imputação múltipla de dados faltantes: uma simulação utilizando dados epidemiológicos. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25:268–78. <https://www.scielo.br/j/ag/a/CYGNN7qsckZYrKFSrSvxNrm/>.

- Shaffer ML, Chinchilli VM. Including multiple imputation in a sensitivity analysis for clinical trials with treatment failures. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007 Feb;28(2):130-7. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16877049/>.

|

ENSAIO CLÍNICO Ex. PMID: 34271271 We performed all the analyses in an intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who had undergone randomization and interventions. Descriptive statistics were applied to present the characteristics of each group with mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile), or the number of cases (%). Either analysis of variance or Chi-square test was used to reveal the baseline balance between groups, depending on the characteristics of the variables. The incidence of post- mastectomy chronic pain at 3 months and 6 months after surgery was compared with an unadjusted chi-square test. Logistic regression models with log links to estimate relative risk (RR) were used to assess RR with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Multiple comparisons between two groups were performed using the Chi-square partition method, in which the type I error was corrected to 0.0125 by the Bonferroni-adjusted method. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P-value of 0.05. In a post- hoc analysis, we assessed the heterogeneity of the treatment effect on post-mastectomy chronic pain at 6 months after surgery across study sites by testing for the treatment-by-site interaction. An interaction term <0.10 suggested potential treatment effect heterogeneity across sites. For missing data, analysis was performed according to a worst-case scenario. In particular, patients lost to follow-up in the two TEAS groups and those in the sham group were considered with and without pain, respectively. Stratified analysis by age, pre-existing pain at the surgery site, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine therapy were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haensel test. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2010). Ex.: PMID: 12004740 Os dados dos participantes foram analisados por intenção de tratamento (intention to treat, ITT). Em casos de dropouts, o valor da última avaliação do participante foi replicado para o dado faltante (last observed carried forward, LOCF). Ex.: PMID: 22968837 In order toaccount for missing data, all analyses were performedusing the ‘last observation carried forward’ method forintention-to-treat analysis. The level of significancewas set at p < 0.05, but when appropriate adjusted tothe 0.01 level to account for potential type I errors. |

Randomização

|

Ex. PMID: 39653805 The individuals included in the study, male or female, defined by chromosomal genotype, were randomized using a tool available on the internet (http://randomization.com), with the generation of a random sequence. Using the permuted block method, every individual was allocated to a single group, with 14 blocks of 6 each, totaling 84. In this way, they had the same probability of being drawn and allocated to one of the 3 study groups: traditional acupuncture (TA), laser acupuncture (LA), and sham laser acupuncture (S-LA). The researcher responsible for the randomization had no other role in this study. Ex. PMID: 30356057 |

Cálculo Amostral

- Normando D et al. Análise do emprego do cálculo amostral e do erro do método em pesquisas científicas publicadas na literatura ortodôntica nacional e internacional. Dental Press J Orthod. 2011;16:33–5. <https://www.scielo.br/j/dpjo/a/Z3nFTVsKKkRD8qSQh3dTqkR/>.

- Röhrig B et al. Sample size calculation in clinical trials: part 13 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 Aug;107(31-32):552-6. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20827353/>.

- Brooks GP, Robert SB. The PEAR Method for Sample Sizes in Multiple Linear Regression. Multiple Linear Regression Viewpoints. 2012; 38(2). <http://glmj.org/archives/articles/Brooks_v38n2.pdf>.

- Whitehead AL et al. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016 Jun;25(3):1057-73. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26092476/>.

- Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceutical Statistics. 2005;4:287–91. <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/pst.185>. PMID: 37744184

- Charan J, Biswas T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J Psychol Med. 2013 Apr;35(2):121-6. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24049221/>.

- Dell RB et al. Sample size determination. ILAR J. 2002;43(4):207-13. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12391396/>.

- Zhong B. How to calculate sample size in randomized controlled trial? J Thorac Dis. 2009 Dec;1(1):51-4. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22263004/>.

- Fraser RA. Inappropriate use of statistical power. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2023 May;58(5):474-477. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36869191/>.

PROGRAMAS

- Programa para Cálculo amostral <http://estatistica.bauru.usp.br/calculoamostral/calculos.php>.

|

FÓRUMULAS N = tamanho da população. n = tamanho da amostra. δ = nível de confiança escolhido, expresso em número de Desvio Padrão (por convenção utiliza 1,96). P =prevalência do fenômeno, ou percentagem (expresso em decimal). Q = percentagem complementar, ou quociente (Q=1-P). e = erro máximo permitido (por convenção se utiliza 3, 4 ou 5).

CÁLCULO AMOSTRAL PARA POPULAÇÃO FINITA n = δ² x P x Q x N / e² (N-1) + (δ² x P x Q).

CÁLCULO AMOSTRAL PARA POPULAÇÃO INFINITA n = δ² x P x Q / e². |

Exemplos:

|

Exemplos:

|

Estudo transversal EX. O processo de amostragem foi estratificado por grupos para ser representativo para a população do estudo. A amostragem probabilística foi realizada em duas etapas, primeiramente por meio de setores censitárias e depois por domicílios, de acordo com as recomendações do Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Para o cálculo final da amostra, foram consideradas estimativa de prevalência de 50%, nível de confiança de 95%, erro máximo de 0,10 e o drawing effect de aproximadamente 2. O tamanho mínimo da amostra para o estudo foi de aproximadamente 400 participantes. A fim de maximizar a representatividade da amostra, 1.557 mulheres foram selecionadas aleatoriamente e entrevistadas. EX. https://www.scielo.br/j/fp/a/LqHfbngt3FfBHbtsxLVBh3r/?lang=en To calculate the sample size, was used a estimated proportion of 50% of the population subgroups with confidence level of 95% in the estimation intervals as well as a sampling error of 10%, and a design effect (DEFF) of 2%. Therefore, the sample size for each group was at least 200 individuals (100 men and 100 women), totaling 600 participants.

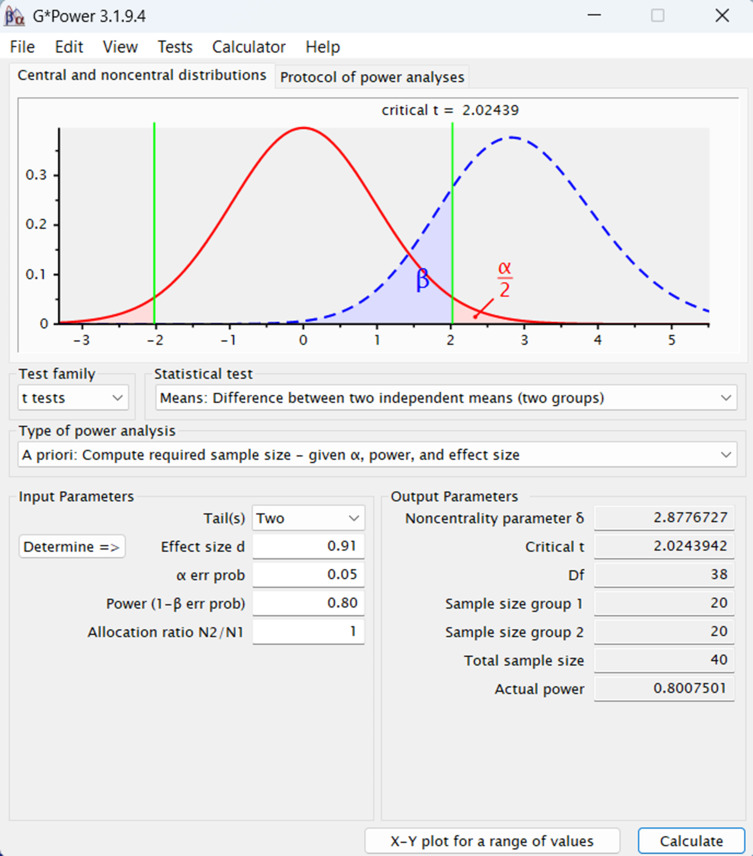

Ensaio clínico EX. PMID: 39804870 The sample size was calculated using G*Power software version 3.1.9.7, with a focus on achieving a robust estimate for detecting clinically meaningful changes. Specifically, a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 11.1 points, with a standard deviation (SD) of 3.8 points, was used based on established values for the primary outcome, the total Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [24]. This estimation considered a power of 80%, an effect size of 0.2, a significance level of 5%, and an anticipated dropout rate of 20% [25, 26]. Consequently, the total calculated sample size was 50 participants, evenly divided into two groups of 25 participants each. KOOS was selected as the primary outcome measure for this study due to its comprehensive assessment of key domains relevant to KOA, including pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, sport and recreation, and quality of life [27]. The tool has been widely validated in populations with KOA and is sensitive to changes following interventions, making it an appropriate and robust measure for capturing patient-reported outcomes in this context [27]. Ex. PMID: 18601750 In calculating the sample size, a power of 90% and an α value of 5% were assumed, to detect a mean change in pain intensity, measured on the 100 mm visual analogue scale, of 32.3 mm between the initial and final values among the experimental group, and a mean reduction of 19.8 mm among the control group (standard deviation 31.9 mm). These assumptions require a sample size of 140 patients per group, in a design with two equal groups. We propose to recruit 400 patients in order to allow for a 30% drop out rate. Ex. PMID: 22732720 A previous study reported a cumulative PONV incidence of 26% to 74% at 24 hours after surgery using prophylaxis with ondansetron and dexamethasone in patients after infratentorial craniotomy. Assuming an incidence of 40%, a sample size of 60 patients was determined by an a priori power analysis to provide an 80% power to be adequate to detect a 25% absolute reduction from 40% in the control group to 15% in the TEAS group at a= 0.05. Ex. PMID: 34271271 The primary hypothesis was that TEAS would reduce chronic pain at 6 months after mastectomy, and combined acupoint stimulation would be more effective than single acupoint stimulation. We calculated that a sample size of 537 participants would have 80% power to detect a difference in the incidence of chronic pain at 6 months after mastectomy among the combined acupoints (25%), single acupoint group (30%), and sham-operated groups (40%), using two degrees of freedom chi-square test with a significance alpha level of 0.05. Considering a dropout rate of 5%, we defined a sample size of 576 participants. Ex. PMID: 39653805 The sample size was calculated considering a difference of 1.5 points between groups, which would be a clinically relevant value for the outcome of neck pain intensity, as measured using the NRS [36], with an estimated standard deviation of 1.6 points, based on a clinical study about cervical pain [17]. The statistical power of 80% and a possible sample loss of 20% were adopted, considering dropouts for any reason. Therefore, 84 individuals were needed, with 28 in each group (TA, LA, and S-LA). The sample size was calculated using Minitab v.17 software (State College, PA, USA). Ex. PMID: 30356057 Ex.: PMID: 32076985 The study was designed to evaluate whether group was noninferior to individual acupuncture for improving pain. The primary outcome was response to treatment, as defined by a 30% or greater improvement on the BPI pain interference measure between baseline and 12 weeks. The margin of noninferiority was defined as an absolute difference of δ = 10% (individual–group) in the proportion of patients who responded to treatment. With a sample size of 282 subjects per group, the study had 80% power with a one-sided α = 2.5% to conclude that group therapy is non-inferior to individual therapy assuming the true response rate in both groups is 35%. To account for a 20% loss to follow-up rate, the target enrollment was 350 patients per arm. Ex. PMID: 40070890

|

Tamanho de Efeito

- Espírito-Santo H, Danie F. Calcular E Apresentar Tamanhos Do Efeito EM Trabalhos Científicos (1): As Limitações Do P < 0,05 Na Análise De Diferenças De Médias De Dois Grupos. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Comportamental e Social. 2015; 1 (1): 3-16. <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2999091>.

- Lopes JM et al. Clinically significant differences: what to choose? Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2020; 78(06). <https://www.scielo.br/j/anp/a/cCjjfFz4qbHqHf8SPTb3Mpg/?lang=en>.

- Grzybowski A, Mianowany M. Statistics in ophthalmology revisited: the (effect) size matters. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018 Nov;96(7):e885-e888. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30187631/>.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect <https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-06>.

- Calculadora para tamanho de efeito em testes não-paramétricos <calculos-tde-kruskal-wallis>.

Cálculo e interpretação do tamanho de efeito da intervenção

|

|

Ensaio clínico Ex. PMID: 39653805 The magnitude of the intergroup difference was calculated using Cliff’s delta (ƍ) [Cliff N, 2014], with classification as not significant (ƍ < 0.147), weak (ƍ < 0.330), médium (ƍ < 0.474), or strong (ƍ ˃ 0.474) [Romano J, Coraggio JS, Kromrey J; 2006]. |

- Effective Rate (ER) = (“total number of patients” – “number of patients without response”) /total number of patients; “no response” is defined as no significant change in VAS score after treatment. (PMID: 37143907)

- The primary outcome was the proportion of participants who showed improvement of 50% or more in symptoms between the groups (the difference in the proportion), as assessed by the ? (Instrument) at ? weeks. The proportions of patients with depression recovery and remission based on the PHQ-9 at 4 weeks. The proportion of participants who achieved a score of less than 5 on the PHQ-9 (indicating depression remission). Participants, No./Total No.(%); RR (95% CI) (11 of 24 participants [46%] in theSA group vs 3 of 23 participants in the NSA group[13%]; RR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.16-3.34; P=.02). Effect size was calculated as RR for dichotomous data. Statistical significance was calculated with Fisher exact test. Intragroup analysis was performed using the Cochran Q test. Intragroup analysis was performed usingth the Friedman analysis of variance test followed by post hoc tests for the differences in PHQ-9 scores at each time point compared with baseline. (PMID: 38032640); (PMID: 35602489); (PMID: 33371123); (PMID: 21178832).

- Proportion Achieving Meaningful Improvement: In addition to the mean change over time in the pain scores, we evaluated the proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful 30% improvement. To compare the proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful response on the RMDQ, NRS, and a global impression of change, the outcomes were dichotomized and tested using χ2 analyses at each point. (PMID: 26903081).

- Therapies were compared with control groups by measuring difference in mean changes in pain and function scores. An alternative experimental design would be based on a “responder analysis,” namely, comparing the proportion of patients within each therapy who experienced a change greater than the MCID. This type of data presentation could bemore informative because it focuses on patients who experience an improvement at least as large as the MCID. This approach is useful when the data are highly skewed by outliers in such a way that the calculated mean value may be above the MCID even when most patients do not have an effect greater than the MCID. (PMID: 25268441).

- The Number Needed to Treat (NNT): is the number of patients you need to treat to prevent one additional bad outcome. Is an absolute effect measure which is interpreted as the number of patients needed to be treated with one therapy versus another for one patient to encounter an additional outcome of interest within a defined period of time. NNT = 1 / Absolute risk reduction (π1 – π0). π0 = risk control group (incidende among non exposed / n group). π1 = risk in treatment group (incidence among exposed / n group). (PMID: 28571585).

Testes estatísticos

Escolha do teste estatístico

- Normando D et al. A escolha do teste estatístico – um tutorial em forma de apresentação em PowerPoint. Dental Press J Orthod. 2010;15:101–6.<http://www.scielo.br/j/dpjo/a/qSQTjRQd4YzWQWSkDmBmspn/?lang=pt>.

- Webmaster P. Dental Press – Guia para a escolha do Teste Estatístico adequado para a pesquisa científica [Internet]. 2016. Disponível em: <https://www.dentalpress.com.br/portal/bioestatistica/>.

- du Prel JB et al. Choosing statistical tests: part 12 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 May;107(19):343-8. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20532129/>.

|

Ensaio clínico Ex. PMID: 34271271 We performed all the analyses in an intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who had undergone randomization and interventions. Descriptive statistics were applied to present the characteristics of each group with mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile), or the number of cases (%). Either analysis of variance or Chi-square test was used to reveal the baseline balance between groups, depending on the characteristics of the variables. The incidence of post- mastectomy chronic pain at 3 months and 6 months after surgery was compared with an unadjusted chi-square test. Logistic regression models with log links to estimate relative risk (RR) were used to assess RR with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Multiple comparisons between two groups were performed using the Chi-square partition method, in which the type I error was corrected to 0.0125 by the Bonferroni-adjusted method. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P-value of 0.05. In a post- hoc analysis, we assessed the heterogeneity of the treatment effect on post-mastectomy chronic pain at 6 months after surgery across study sites by testing for the treatment-by-site interaction. An interaction term <0.10 suggested potential treatment effect heterogeneity across sites. For missing data, analysis was performed according to a worst-case scenario. In particular, patients lost to follow-up in the two TEAS groups and those in the sham group were considered with and without pain, respectively. Stratified analysis by age, pre-existing pain at the surgery site, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine therapy were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haensel test. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., 2010). Ex. PMID: 39653805 The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to evaluate data normality. Data for the PPT and CPM, which presented normal distributions, were presented using means and standard deviations, together with the application of analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures, assuming a significance level of p<0.05. Data for the NRS, TS, and GPE, with non-normal distributions, were reported as pre- and post-treatment medians and Q3-Q1 interquartile ranges, difference scores (before– after), and the differences between them. The Kruskal-Wallis test was applied, with the posthoc Mann-Whitney U test for comparison between groups. The Mann-Whitney U test results were considered significant only for values below 0.0166 (Bonferroni correction: 0.05/3). The magnitude of the intergroup difference was calculated using Cliff’s delta (ƍ) [Cliff N, 2014], with classification as not significant (ƍ < 0.147), weak (ƍ < 0.330), médium (ƍ < 0.474), or strong (ƍ ˃ 0.474) [Romano J, Coraggio JS, Kromrey J; 2006]. Data processing employed the IBM SPSS Statistics v.19 for Windows software package. PMID: 30356057 Data entry was carried out twice. Analysis was performed with the SPSS statistical software system (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL; version 23.0). Fisher test was used to compare binary outcomes between the control and the intervention groups. Metric-variables were assessed for normal-distribution by Kolmogorov- Smirnov-Test. For normally distributed variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for descriptive analyses, and groups were compared by an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The unpaired t-Test was used for post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Influence of group x time of the state anxiety was assessed by ANOVA for repeated measures with group as between subject factor. In case of a non-normal distribution, non-parametric analyses were performed with descriptive statistics given as median (M) and interquartile-range (IQR). Kruskal-Wallis-Test was used for intergroup comparisons. Dunn’s Test was used for post-hoc pairwise group comparisons. |

Testes de correlação

-

-

- Miot HA. Análise de correlação em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J vasc bras. 2018;17:275–9. <https://www.scielo.br/j/jvb/a/YwjG3GsXpBFrZLQhFQG45Rb/?lang=pt>.

-

- Kappa:

-

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977 Mar;33(1):159-74. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/843571/>.

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276-82. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23092060/>.

- Xie Q. Agree or Disagree? A Demonstration of An Alternative Statistic to Cohen’s Kappa for Measuring the Extent and Reliability of Agreement between Observers. 2013. <https://nces.ed.gov/FCSM/pdf/J4_Xie_2013FCSM.pdf>.

-

Testes de regressão

Regressão linear simples:

-

-

- Castro1 2, Ferreira1 3. Linear and logistic regression models: when to use and how to interpret them? 2022; <https://www.jbp.org.br/details/3779/pt-BR/modelos-de-regressao-linear-e-logistica–quando-utiliza-los-e-como-interpreta-los->.

- Castro HM, Ferreira JC. Modelos de regressão linear e logística: quando utilizá-los e como interpretá-los? J bras pneumol. 2023;48:e20220439. <https://www.scielo.br/j/jbpneu/a/8ddLBhmCQZpS7bhqwywFWTB/?lang=pt>.

- Schneider A et al. Linear regression analysis: part 14 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010 Nov;107(44):776-82. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21116397/>.

- <https://docs.ufpr.br/~lucambio/CE225/2S2011/texto_2010.pdf>.

- Kim JH. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019 Dec;72(6):558-569. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31304696/>.

- Daye ZJ, Chen J, Li H. High-Dimensional Heteroscedastic Regression with an Application to eQTL Data Analysis. Biometrics. 2012 Mar;68(1):316-326. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22547833/>.

- Kroll MH, Emancipator K. A theoretical evaluation of linearity. Clin Chem. 1993 Mar;39(3):405-13. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8448849/>.

- Emancipator K, Kroll MH. A quantitative measure of nonlinearity. Clin Chem. 1993 May;39(5):766-72. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8485866/>.

-

|

Análises bivariadas e múltiplas foram utilizadas para averiguar os fatores associados aos domínios da QV. Na análise bivariada realizou-se regressão linear simples para verificar associação entre as variáveis independentes e os domínios (variáveis dependentes). A seguir, variáveis com p-valor ≤ 0,20 na análise bivariada foram incluídas no modelo de regressão linear múltipla para ajuste das variáveis confundidoras (Schneider A et al., 2010). O método de entrada das variáveis foi feito em etapa única. A magnitude das associações foi apresentada em coeficiente de regressão não ajustado (β) com respectivos IC 95%. Os modelos foram avaliados e validados quanto aos seguintes pressupostos da regressão linear: (i) multicolinearidade pelo fator de inflação de variância (FIV) – considerou-se ausência de multicolinearidade FIV médio < 5,0 (Kim JH et al., 2019); normalidade dos resíduos pelo teste K-S, adotando valores de p do teste > 0,05 (Ghasemi A; Zahediasl S, 2012); (iii) homocedasticidade, avaliada pelo teste de Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg – a homocedasticidade dos modelos foi confirmada quando valor de p > 0,05 (Daye ZJ et al., 2012); e (iv) linearidade analisada pela visualização gráfica (26). |

Regressão linear múltipla:

-

- Marill KA. Advanced statistics: linear regression, part II: multiple linear regression. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 Jan;11(1):94-102. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14709437/>.

Regressão logística:

-

- Fernandes AAT et al. Leia este artigo se você quiser aprender regressão logística. Rev Sociol Polit. 2021;28:006. <https://www.scielo.br/j/rsocp/a/RWjPthhKDYbFQYydbDr3MgH/?lang=pt>.

- DeMaris A. A Tutorial in Logistic Regression. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57:956–68. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/353415>.

- Sperandei S. Understanding logistic regression analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2014;24:12–8. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24627710/>.

- Harris JK. Primer on binary logistic regression. Fam Med Community Health. 2021;9:e001290.<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8710907/>.

Testes de comparação

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM):

-

- Brown VA. An Introduction to Linear Mixed-Effects Modeling in R. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 2021;4:251524592096035. <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2515245920960351>.

- Kumle L et al. Estimating power in (generalized) linear mixed models: An open introduction and tutorial in R. Behav Res Methods. 2021 May 5. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33954914/>.

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: a generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988 Dec;44(4):1049-60. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3233245/>.

The Mixed Model of Repeated Measures (MMRM):

-

- Muhammad LN. Guidelines for repeated measures statistical analysis approaches with basic science research considerations. J Clin Invest. 2023 Jun 1;133(11):e171058. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37259921/>.

- Schuler A. Mixed Models for Repeated Measures Should Include Time-by-Covariate Interactions to Assure Power Gains and Robustness Against Dropout Bias Relative to Complete-Case ANCOVA. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2022 Jan;56(1):145-154. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34674187/>.

- Gosho M, Maruo K. An application of the mixed-effects model and pattern mixture model to treatment groups with differential missingness suspected not-missing-at-random. Pharm Stat. 2021 Jan;20(1):93-108. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33249763/>.

- Bell ML, Rabe BA. The mixed model for repeated measures for cluster randomized trials: a simulation study investigating bias and type I error with missing continuous data. Trials. 2020 Feb 7;21(1):148. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32033617/>.

- Donohue MC, Aisen PS. Mixed model of repeated measures versus slope models in Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012 Apr;16(4):360-4. <https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22499459/>.

|

Ex.: Kawi et al., 2025. PMID: 40152243 [3 Braços] Intention-to-treat was used with 2-sided tests of α¼0.05. Baseline characteristics were compared using analysis of variance (continuous variables) and χ2 tests or Fisher exact tests (categorical variables). Mixed models for repeated measures (MMRM) for continuous outcomes and generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) for dichotomous outcomes were used to examine study outcomes by appropriately specifying the contrast parameters. The dependent variables for MMRM included the change score of the study’s primary outcomes from baseline, and the independent variables included group, time, and group-by-time. An unstructured covariance was used to account for the correlation of repeated measurements within participants. The MMRM provided an unbiased estimate for missing data (missing at random), so we did not impute missing values. Data were analyzed for up to 6M follow-up. To compare the proportion of participants with a clinically meaningful response (ie, responder analysis), the primary outcomes were dichotomized and tested using GLMM. Responders were defined as achieving more than 1.5 points of pain reduction from baseline or more than 2.5 points improvement from baseline in function. Sensitivity analyses were used to assess the robustness of the study conclusions at 1M follow-up for the primary outcomes (see the Supplementary Material for details). Analyses for the primary outcomes were not adjusted for multiple tests because the 2 primary outcomes, pain and function, quantify different aspects of treatment effects. All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 and R-4.2.0. No interim analyses were conducted. |

Programas

- Randomização: <http://randomization.com>.

- Cálculo amostral: <http://estatistica.bauru.usp.br/calculoamostral/calculos.php>; <https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm>.

- Poder do teste estatístico: <https://stats.oarc.ucla.edu/other/gpower/>.

- Tamanho de efeito: <https://pedro.org.au/portuguese/resources/confidence-interval-calculator/>; <https://www.socscistatistics.com/effectsize/default3.aspx>.

- Calculadora para tamanho de efeito em testes não-paramétricos: <calculos-tde-kruskal-wallis>.

- Análise estatística: